Long study drives down dirt disease

Thirty years of progress has been made in the understanding and treatment of the soil-dwelling melioidosis disease.

Thirty years of progress has been made in the understanding and treatment of the soil-dwelling melioidosis disease.

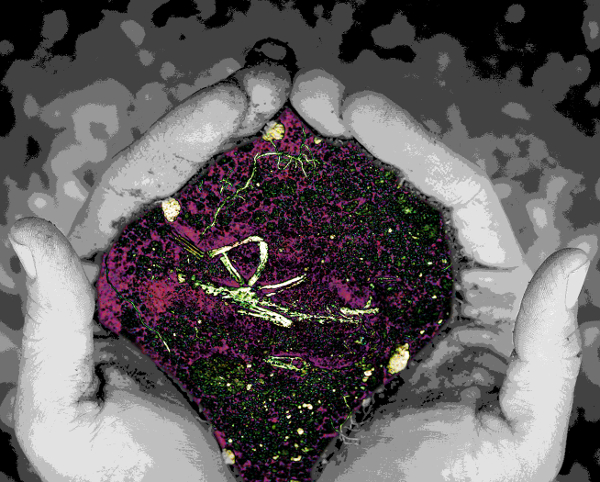

Melioidosis is caused by bacteria that live below the soil’s surface during dry weather, but after heavy rainfall proliferate and are found in surface water and mud.

People can easily catch the disease through small cuts and scrapes that come into contact with dirt or mud.

For the last 30 years, the Darwin Prospective Melioidosis Study (DPMS) has been gathering data on the issue and informing new treatments.

In a new paper based on the DPMS, experts find that the mortality rate of melioidosis in Darwin has decreased from 31 to six per cent.

The overall number of cases has risen over the study period, which has been linked to a combination of population increase, more awareness leading to more tests and diagnosis, and more construction activity in the Top End, which disrupts the soil and releases the bacteria.

The ongoing research shows the bacteria generally causes serious illness in those with underlying health problems, while healthy people should not die if diagnosed and treated early.

Professor Bart Currie from Menzies School of Health Research (Menzies) and Royal Darwin Hospital (RDH) says the 30-year DPMS shows the importance of recognising diabetes and hazardous alcohol use as major risk factors for the severity of melioidosis, but also at risk are those on immune-suppressing therapy including cancer patients.

“This is what the RDH microbiology laboratory, Infectious Diseases Department and ICU have learnt and the 2020 Darwin melioidosis treatment guideline is now used internationally, for instance in the USA with recent cases of melioidosis,” Dr Currie says.

“Analysis of our 30 years of cases and links to weather also provides consistent evidence that global warming is likely to increase the risk of melioidosis in the future and expand the boundaries southward.

“With colleagues in Australia and overseas, we also have found that there are unexpected instances of melioidosis outside the tropics and more work is needed to understand these occurrences.”

Research on the genetics of the melioidosis-causing bacteria have shown that it originated here in Australia and then spread to Asia, then to Africa and then more recently to the Americas.

“There is much more work to be done as even in the Darwin study we have found ‘Asian’ strains that have entered Australia in recent decades, but how and from where specifically we don't yet know,” Dr Currie said.

“Similar recent findings of a cluster of three cases of ‘imported’ melioidosis in the USA shows how important it is for there to be a ‘global’ view on melioidosis and for international collaborations to share findings and data to better understand this enigmatic infectious disease.”

The Darwin study also provides evidence that the bacteria can become airborne during monsoonal weather events and cause melioidosis through inhalation.

The experts say global warming is likely to increase the risk of melioidosis in the future, boosted by a combination of warmer temperatures, higher humidity and increased rainfall.

Print

Print